This text is an account of time spent in the Atacama Desert in September 2023. I lived with an Indigenous Lickan Antay (Atacameño) community in Coyo to complete field research. It is the driest place on earth and at 2400m above sea level people have adapted to the intense UV radiation, lack of water, salty grounds, and extreme conditions. I was hosted by members of the community in a home that was built by hand with mud, river stones, wood and recycled materials. The house was surrounded by a garden within an oasis filled with native trees, medicinal plants, herbs, and cultivated crops. They live a nomadic life, spending time between the different ‘Ayus’ (settlements) and ‘Estancia’ (stables) with their animals; goats, llamas, donkeys and shepherd dogs. Our indigenous host was known for using his ancestors’ traditional methods with plants and the elements to heal locals. His partner was from a family of nomadic llama herders, who manage to keep animals in one of the harshest environments on earth. She learnt from her grandmother and mother and is one the few herders still passing traditions to her daughters and sharing the importance of the culture. The llamas feed on the desert plants Cachiyuyu and Tamarugo. The Cachiyuyu absorbs salt from the land so that vegetation can grow there.

This text considers the relationship between the unique landscape of the desert and the identity of the indigenous people and my own as an autoethnographic researcher. I would like to thank the people of Coyo for hosting me on their land and for sharing their vast knowledge. I would like to acknowledge the privileged position that enabled me to spend time with them.

With thanks to support from La Wayaka, CCRI Foundation and The University of Gloucestershire.

The Overview Effect

I left London in the dark and arrived in Santiago in darkness. Flying over the Andes extra measures such as early landing procedures and slower flight times, had to be put in place due to the turbulence caused by the mountains.

Santiago’s unique position surrounded by the Andes was striking. I was stuck by the greenery in public space, much of it Crassula ovata. An exotic and expensive houseplant in the west, grown everywhere there like a weed. (See left image Crassula ovata (Jade plant) in Santiago)

Santiago, would soon become a distant world, far from the starkness and varied landscapes of the Atacama.

I flew out of Santiago in the rain; I would come to miss and be grateful for. Flying to Calama the vastness of the landscape stretched out underneath, salt flats like the whites of waves, cracks formed and shifted below and at times the earth looked like it was slipping underneath itself. I finally began to see signs of human activity, the copper and lithium mines, and vast expanses of solar panels also containing the latter. There were mostly men in the airport- miners flying in for two-week stints. Their trucks had bent antennae on them to aid reception in isolated locations, some had solar panels attached. I got the feeling that they were caught between the delicate balance of the ecological impact of mining and equal benefits of employment. The indigenous communities constantly fight to keep ancestral land from mining companies, who use water intensive extractive processes to supply global demand for electric batteries, the disputable future of ‘greener energy’.

I met the other artists with whom I would be sharing this three-week experience. Two of the group had spent time in the desert already exploring the deserted mining towns which were abandoned when it became too toxic and when nitrates could be made chemically instead. We left the airport at sunset, a field of wind turbines with red flashing lights at their centre appeared before we were plunged into darkness, feeling the vastness of the desert without the help of sight, stretching out 104,741square km ahead of us. I often focused in the desert on that straight flat line in the vast open expanses and the fragmented and sweeping lines created by the rock formations that resembled the bottom of the sea, or the terrain of another planet.. The Atacama terrain so closely resembles that of Mars it was used to test the Mars Rover in 2017.

At times the horizon would seem like it was moving due to the haze. Different atmospheric temperatures cause the atmosphere to refract the light to become a refracting lens which produces distorted optical effects.

(Image- top bleed and left Hiking in Catarpe, Chile)

Reciprocity

On the first morning we woke at sunrise to meet our indigenous hosts and to take part in a ceremony called an Ayni (meaning reciprocity in the native language Kunza). Our offering of coca leaves and wine was placed in ancestral ceramic cups with faces on to represent female and male energy on a diamond shaped blanket in line with the nearby volcano, Licancabur. Our offering of organic food was then poured along with the contents of the jugs into a mound in the ground by a fire of smoking herbs and coca leaves. The sun appeared from behind the mountains, tickling the horizon, before it burst through and began to warm us.

People in the desert have practiced these cultural traditions and way of life for over 10,000 years. This layered history is represented by petroglyphs near Coyo which date back to different time periods. The region has always been a transit route with people passing through from faraway places like the Amazon. The Atacameño people take part in this ceremony when they first arrive at a place to connect with Mother Earth and to thank the mountains for protecting them. Rituals and ceremonies are often communal, reinforcing a spiritual connection to the unique landscape.

Cosmology

We had to finish most of the excursions in the desert before sunset as the roads are so bumpy and hard to navigate. As darkness fell the Andes were transformed into a purple hue. We spent our nights beneath the blanket of the spectacular stars of the southern hemisphere, the upside-down Milky Way. The night sky had such depth.

In the Atacama, I felt a strong connection between the geological and cosmological, the future and the past. I visited Tulor, the first Lickan Antay settlement. They used bones to strengthen the structures of their mud and straw adobe structures- a process still used today. I also learnt about more recent history, such as the 1973 military coup, and the missing people who disappeared in the Atacama. This relationship between memory, the ground and the skies is so powerfully captured in Patricio Guzmán’s Nostalgia for the Light. It conveys the story of the women who still search for their lost relatives in the vast expanses of the desert many decades later.

Water

The Atacemeño people consider themselves a water culture. I became fascinated by the sophisticated terracing and irrigation systems for crop cultivation to maximize water usage where there is scarcity. (Image below left Terracing and Irrigation Systems)

(Image left - Embodied Land, unfired river clay, straw, found branches, dimensions variable, 2023 )

These two sculptures are offerings inspired by the Ayni. Creaturelike or grown out of the land, they also reference flower arrangements in a place where cut flowers are a rare luxury and where dried flowers are used to pay respects to the dead.

The second ritual we experienced was the Tezmazcol (vapour bath ceremony). A ceremony of all the elements. Our host set a diagonal mat up in front of the fire containing volcanic rocks and pots of local herbs. We had to cleanse ourselves with coca leaves in front of the fire, to blow on them and put them in the flames to cleanse our energy. We then went into the sweat lodge in the garden. Volcanic rocks were brought in every five minutes adding herbal water over the rocks to release the steam for forty minutes.

(Image left-Tulor Postholes)

The Atacameño community is centred around adaptation and resilience. Their cosmovision has evolved over time, adapting to changes and external influences while preserving the core values passed down from ancestors. This complex belief system guides their way of life and their understanding of their position within the universe. It reflects the deep connection between humans and nature which forms their cultural identity. One night when camping in the desert, our hosts showed us their ancestral astronomical map and taught us about Andean astronomy where they look for the darkness and not the stars.

The Atacama is used for same reasons as people in the past but now with technology. One morning, there were clouds in the sky for the first time. We visited Alma, the largest astronomical project in the world where astronomers observe the night sky in an invisible array of light. This location is the best place for the observatory as the high altitude at 5000m means there is less distortion. They operate 24 hours a day so light pollution isn’t a problem, but in this high, flat, and dry place they get clearer images. Alma is accessible for machines to come from overseas, the big antennae came in half, along closed highways from the nearest port over 300km away. The images look like electro cardiograms (i.e., you see the frequency). They receive graphic data and interpret it, like recognisable fingerprints. This project involves 25 countries working together. I found myself wondering If only there could be the same collaboration and investment towards climate change.

A few days into our stay, I woke up and went outside and the soil was wet. I thought maybe it had rained but that only happens around two days a year and in some parts of the Atacama never. It was irrigation day and the house had been allowed to turn on the water briefly. In the eighties the Chilean government made a law so water could be owned. The Atacameño (Lickan Antay) people bought whole stretches of the river to protect it. They now distribute water every twenty-one days to each community.

I began to source materials locally as a way to understand the landscape. I started to prepare the clay for use from the dried river. I also made cyanotypes in the garden using wastewater to get to know the local materials, experimenting using salt crystals and soil.

(Image below left- Dried-up river in Coyo)

(Image Left- Finding Water, Desert Plants, Fabric and String. Dimensions Variable, 2023)

This work focuses on the way that the trees in the desert form large root systems to access subterranean water.

(Image left- Algorrobo Tree)

The forms within the sculpture also reference the watery networks below the volcanic soils of the Atacama that feed the salt lagoons. I started to make works based on tools to find water called water dowsers and then made a series of sculptures that are balanced precariously. The idea of balance within nature was something that seemed very important to the Atacemeño community.

(Image left- Finding Water, Performance stills on photographic paper, A4, 2023)

I took sculptural works to the desert to perform with, connecting through my body with the materials and the landscape. This body of works references Astrida Neimanis’s book Bodies of Water which imagines the human body, the water catchment, and its surrounds as interconnected channels. By understanding our human bodies as bodies of water- flowing into other bodies of water it places us in a different relation to water as a material and as inseparable from nature.

(Image left- Holding Water, Glazed ceramics pit fired using clay dug from the river in Coyo, with copper sulphate, salt ash and charcoal glaze. Dimensions variable, 2023)

These works are vessels to hold water or local plants and food that sustains life in the desert. They are small enough to be handheld, referencing the objects our ancestors would have made to carry with them. Often objects of most importance. The word holding in the title is a direct reference to Ursula Le Guin’s Carrier Bag Theory which Neimanis refers to within her text, proposing the carrier bag as the first human tool and stressing the importance of items to carry and to hold.

Salt

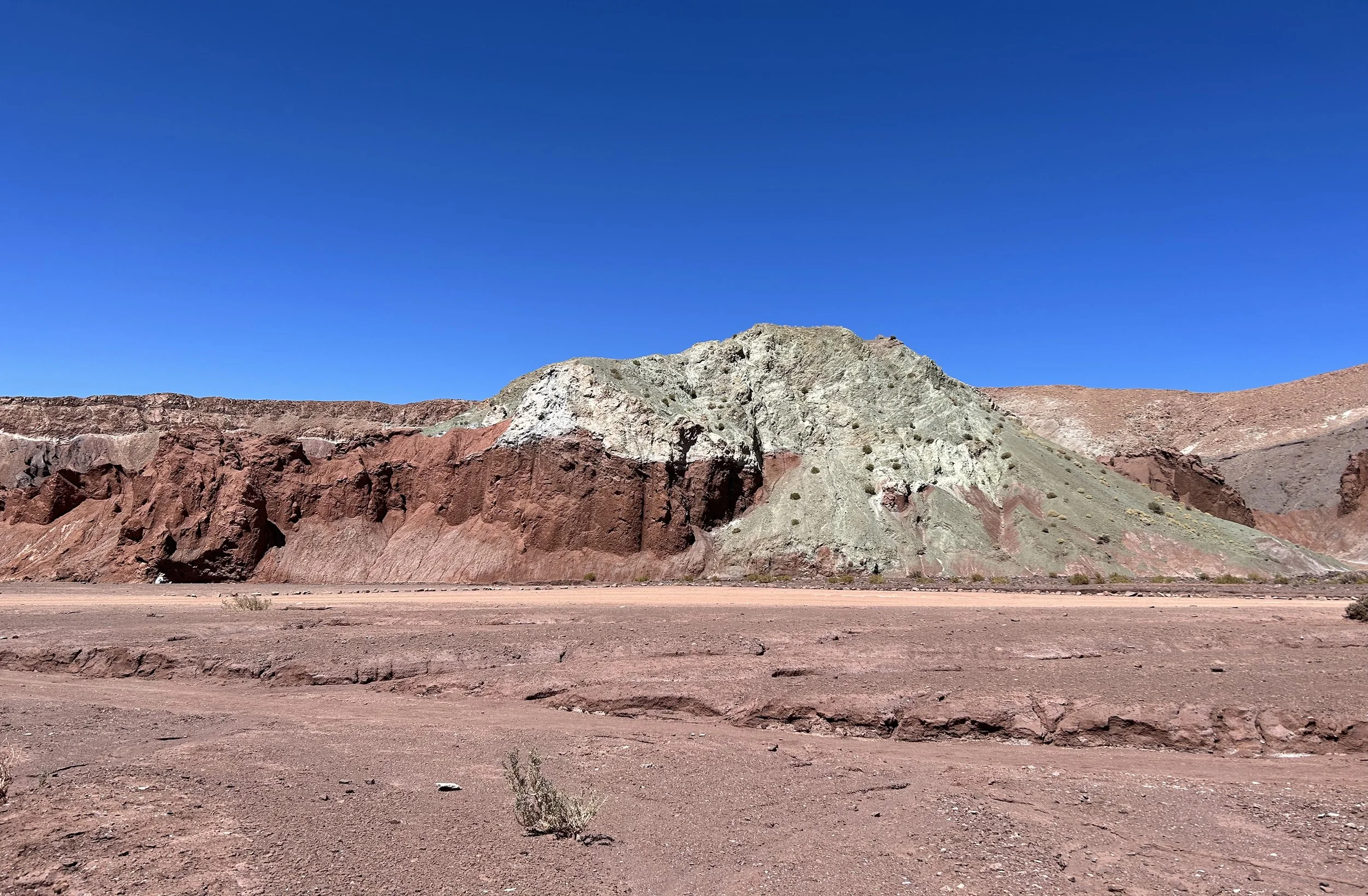

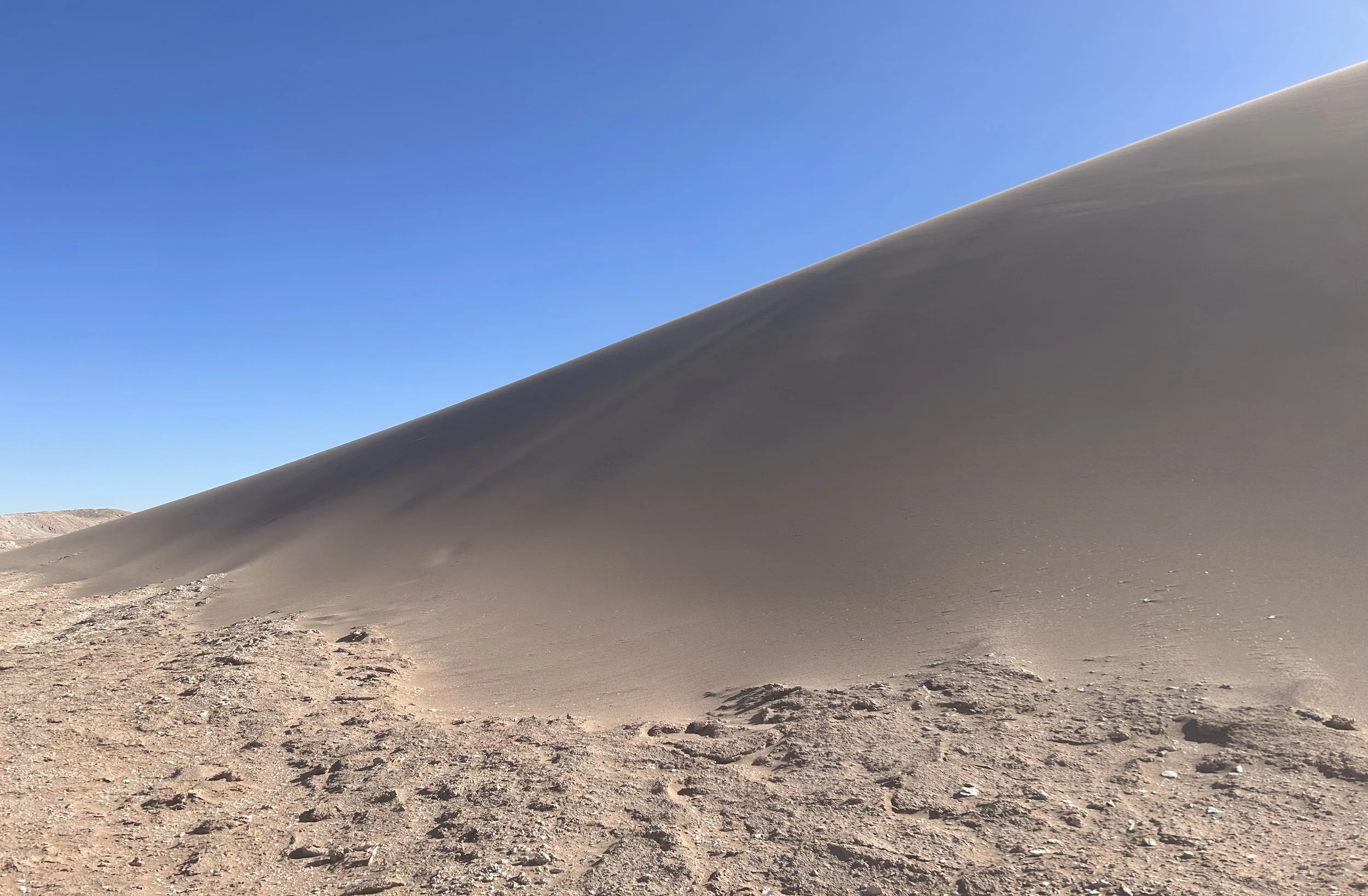

We went on an excursion to the Valley of The Moon, to see the salt mountains formed 20,000 million years ago with their sand dunes and crystallised rocks. Small dust tornados in the distance were forming and Lascar the only active volcano in the area was smoking from its top. It is the father of the mountains in the area and erupted earlier this year. Both these were frequent memorable sights during our stay. (Images below Valle de la Luna, Chile(Valley of the Moon)

We also visited the salt flats (Salar) and learnt about the subterranean river that feeds it. Thanks to the Lickan Antay people it is now a protected ecosystem with endemic life within. It is known that everything is connected within this underground system because organisms from the sea have been found in volcanoes. This is why the water in desert never dries up because it doesn’t depend on rain. The air was so salty, and we faced 11 on the UV index, the highest possible score. Our host explained to us that the salars are important for the ecosystem because they turn carbon-dioxide into oxygen twenty-four hours a day. This is more than rainforests produce per square km. (Image below- Salar de Atacama (Salt Flats)

Adaptive Algae

We went across the border to Bolivia for the day. Our driver had to fill up the petrol from the roof because stations were few and far between. We had to pass through three passport controls, and it was much colder and even more vast with no road markings or signs. We saw 18m high stones which had been caused by volcanic activity and shaped by the wind. Laguna Colarada is home to around 25,000 flamingos who live on the plankton. The red water is caused by a type of algae that has adapted to be able to resist the extreme heat at high altitudes. The normally white flamingos turn pink due to the algae. (Images below - Laguna Colorada, Bolivia)

The effects of being at over 4000m were strong. In Coyo water took much longer to boil and we had grown used to our skin feeling dry but here all our food packets puffed up and the bananas ripened and exploded. We passed by a check point to stop smugglers and saw the white and green lagoons, one was white from borax and one green from iron. There’s so little water in this region between Chile and Bolivia but it’s some of the most beautiful I’ve ever seen. (Image below- Laguna Verde, Bolivia (Green Lake)

We tried to go to see the lithium mines knowing we might not be able to see much due to strict access rules but hoping to get an understanding of the mine and the size of the Salar. I kept getting electric shocks from all the static on the journey. On the way we saw so much more grass as we travelled through the planted forest of Tamarugo trees which help to stop desertification. There were indigenous communities near to the border of Argentina and very close to the mines.

There are roads on the Salar but only for mining vehicles to go to Antofagasta. In Chile, lithium is abundant mineral is in the brine but in other countries it’s in the rocks so it's more expensive and harder to extract. The intense sunlight in the Atacama makes the process of lithium extraction by evaporation faster. We saw the vast salt piles marking the pool edges which result from this process. The ground on the salt planes sounded hollow when you threw something onto the ground as underneath the surface it’s water.

Back in Coyo we began to feel the change of season. The blossom and shoots were breaking through the desert surface. It’s warmer now at night. We went to the Altiplano (Andean Plateau) and saw three types of flamingos. Some fly all over the world, some to Africa and some only in Chile. Apparently in the winter the water is frozen and during the day they move but at night the water freezes around them. The Altiplano meaning high plane, is the largest high plateau on earth except for Tibet. It is in the widest part of the Andes. The largest part of the Antiplano is in Bolivia, the most norther in Peru and the southwestern in Chile.

The Volcano

We went to the Valley of the Cactus, and saw over 2m tall cacti, some had sections that were dried up showing a mesh-like core. They grow about 2cm a year. (Image below- Guatin, Chile (Valley of the Cactus)

We visited the Rainbow Valley with the rock formations of copper and sulphur. (Image below- Valle Acoiris, Chile. (Rainbow Valley)

(Image left- Volcan, Glazed ceramics, dimensions variable, 2023)

This led me to make ceramic works to try to encapsulate them and the nearby volcanos.

These works pay homage to the significance of the volcano which became an orientation point wherever we were in the desert, an energy that resonated throughout the land. Its size refers to the proto volcanos we saw when travelling around the region, becoming prototypes for larger sculptural works.

Full Circle

I had slowly begun to know the desert, walking out into the spaces taking tentative steps in the heat and altitude, making it difficult to breath at times. Distances became so hard to ascertain- walking towards something only to feel it got further away. I couldn’t imagine what it must be like to be desperate in the desert for water, seeing a mirage to then realise it was an illusion.

On the final day, I got up at sunrise to go to the pool where water is collected for the communities. Time had felt different, there was a slowness to things in the desert. Marks made weeks ago, are still there in the dust. I said goodbye to the community, the landscape and the llamas and animals that I had formed a close relationship to.

Flying back to Santiago over the desert at sunset, seeing the blinking red lights on the turbines again but from the runway this time and then heading back to the UK over the Andes, so vast, with so much snow, so different from in the desert. They seemed to go on forever.

I know that I will continue to make work about this otherworldly place and to tell of my experiences learning about life in the Atacama for a long time to come. I see the Atacama and the fact that people live there despite the extreme elemental forces as an example of a hopeful future with regards to climate change.